A March 2018 photo of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers.

A March 2018 photo of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers.

Mari*

"Mari" is a U.S. citizen who has struggled for the last 6 months to keep her home and her health since her husband was taken and detained by immigration officials, despite being in the middle of an asylum case.

We have changed Mari’s name because she is afraid of retribution for telling her story.

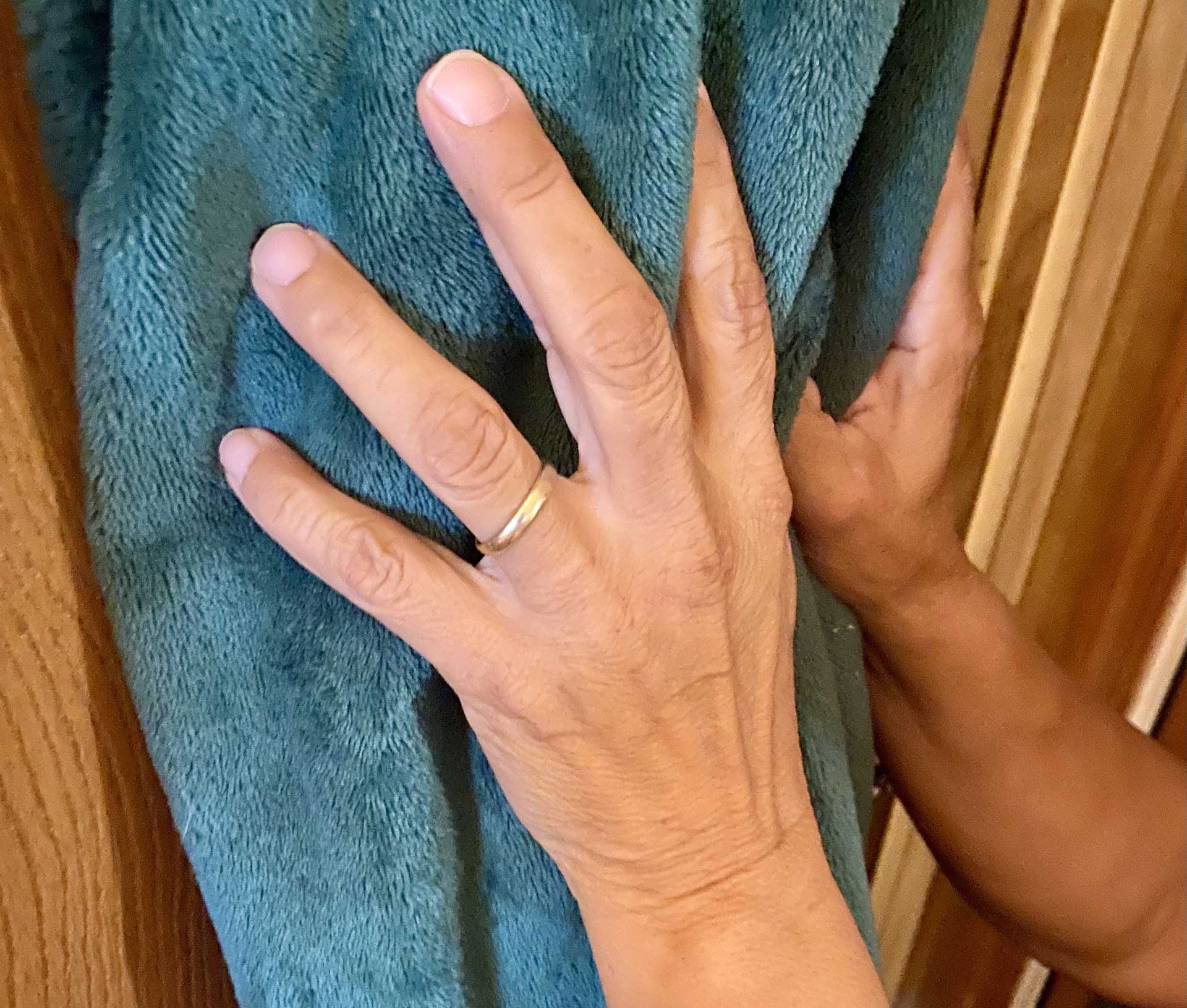

VIEW LARGER Mari keeps her husband's robe hanging in their room where he left it — ready for him if, and when, he comes home.

VIEW LARGER Mari keeps her husband's robe hanging in their room where he left it — ready for him if, and when, he comes home. When I met Mari, in April, her husband had been detained for about two months. She was afraid of losing their home without his income. Her mental and physical health were deteriorating, and she was worried about her son’s wellbeing.

Unable to work because of her ongoing health issues, Mari is still scrambling to pay the family’s bills every month. They gets some money from her son’s disability checks, she’s done garage sales, and family friends have pitched in and started a GoFundMe.

In May, she said her only hope is that he will get released soon, on bond.

“He does not have a criminal background,” she said. “I don't understand what benefit they have holding him in there when he could be out here, actually taking care of me, his wife.”

Mari has ongoing health issues that have only gotten worse in her husband’s absence. When we spoke, she was having surgery that week.

“Which I will need his total support and care for,” she said. “Also when I'm going through this surgery, my husband is also the guardian of my son who is mentally challenged. And who will be taking care of my son? Because I will not be able to get out of bed and take care of him… Because the way I see it, they're putting my life and my son’s life in danger by not letting my husband come home and be with us.”

The Trump administration is detaining people who don’t have criminal backgrounds, and in many cases who, like Mari’s husband, were following the legal immigration process. Separating families could exacerbate any financial strain they are under and impact the broader economy.

Yale University’s non-partisan Budget Lab estimates. that unauthorized immigrant workers paid about $66 billion in federal taxes in 2023 alone. And the Center for Migration Studies says about 4.7 million U.S. households are mixed‑immigration-status and consist of at least one undocumented person and one citizen or legal resident.

Mari’s husband has lived in the U.S. for about 30 years — after crossing the border unauthorized with his family when he was a teen. He started an immigration case in 2022, pursuing humanitarian protections akin to asylum. He received a work permit and was waiting for a judge to hear his case when agents unexpectedly arrived at his home one morning, and, guns drawn, took him into custody.

“My husband is not a flight risk,” Mari said. “He is not going to run. He was complying 100% with ICE, with his check-ins, with communicating by phone.”

Her husband had a few hearings where Mari was hopeful he would be released. Family friend Jennie Mullins said those hopes were dashed when the judge gave him a mandatory 150 day detention before he could be eligible for bond.

“And she's facing a surgery tomorrow without him by her side, and it's really a severe hardship and traumatic experience for her and the family,” Mullins said when we spoke at Mari’s home in May. “It's cruel and it's inhumane and it's completely unnecessary.”

Mullins said the family’s lawyer applied for his bond, which they hope will go through this month. But they don’t yet know how it could be affected by recent news.

The Washington Post reported that Immigration and Customs Enforcement acting director Todd Lyons told staff that immigration judges can no longer grant bond to detainees. Only Homeland Security officials can decide whether someone should be released.

I asked Mari if she and her husband ever talk about what they will do if he is deported. She said that is not an option they want to consider.

“We have a lot of faith in God, that God will make things the way they have to be, and that they will eventually release him here in the United States,” she said. “Because, like I said before, deporting my husband to Mexico is actually sentencing him to death, and he's not a criminal to be sentenced to death.”

As a teen, he and his family fled death threats from organized criminal groups in Mexico. His family has never felt it was safe to return.

Jennie told me last week that Mari had been in the hospital again. She collapsed in her home and her grandson called an ambulance. After a few days at St. Mary’s, doctors said she was well enough — for now — to go home.

Reydi

Reydi is a Venezuelan man who came into the United States in 2022 under a humanitarian parole started by the Biden administration, which President Donald Trump recently canceled — putting many in his position at risk.

VIEW LARGER Local newspapers in Honduras display stories of violence towards the LGBTQ Community. (2018)

VIEW LARGER Local newspapers in Honduras display stories of violence towards the LGBTQ Community. (2018) I met Reydi in November of 2022 in a migrant shelter in Nogales, Sonora.

Then-President Joe Biden had just announced a new immigration rule that expelled most unauthorized Venezuelan migrants to Mexico while expanding options for legal entry. Many Venezuelans, including Reydi, were fleeing a deepening humanitarian crisis driven by economic collapse, political repression, and government-sanctioned violence.

Reydi arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in Nogales and connected with the nonprofit Kino Border Initiative. They found him pro bono legal help, and he eventually got humanitarian parole into the U.S. For the last two-and-a-half years, he’s been living in New York.

Trump ended the CHNV humanitarian parole program that allowed Reydi to be in the country legally and to work. More than half a million people — from four countries experiencing extreme instability: Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela — had arrived lawfully and were granted parole under that process.

But Reydi was able to maintain his legal status and work permit because he had already started an asylum claim.

Before leaving South America due to politically-motivated violence and homophobic attacks, Reydi had finished his law degree and was teaching at a university. In New York, he has a maintenance job.

He says not everyone in his position — legally in the country through parole programs like CHNV — had started or continued the asylum process.

"Many people, in my view, thought that it was going to be renewed every two years,” he said in Spanish, speaking over the phone. “And in reality, that wasn’t the case, because the new administration went ahead and canceled it outright."

Reydi says his background in law gave him an advantage to navigate the legal system, but the immigration process can be very confusing.

Reydi has had four hearings in his asylum case, but his next isn’t until fall of 2027.

"I’m trying to gather all the evidence from my perspective, from everything I went through, the situations I had to endure in Venezuela — every experience I lived through. So I’m sort of mapping everything out over time, so that when I give it to the lawyer, it’ll be a bit easier for them to handle the case. Because I don’t want it to include anything other than what I truly lived, what I went through."

Reydi’s story started with political persecution in Venezuela, to escaping homophobic attacks in Ecuador with his then-partner. They made the treacherous migration through the Darian Gap, Central America and Mexico, and were finally separated when crossing the U.S.-Mexico border unauthorized. All before Reydi gained humanitarian parole and reunited with his boyfriend in New York.

Reydi hopes I can make it to his asylum hearing in 2027. He wants to keep sharing his story.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.